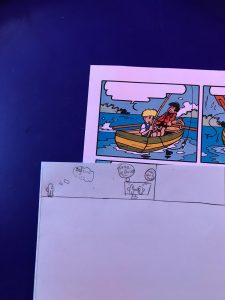

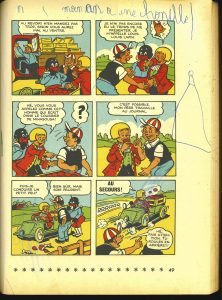

À 5 ans, Alain ouvre son premier grand Journal, TARZAN, lancé, comme le journal TINTIN, en septembre 1946. L’un propose des récits d’importation bariolés, l’autre des récits locaux aux couleurs bon ton. L’un est décrié par les éducateurs, l’autre les courtise. Tous ces illustrés ont pour support le papier pulpe, fourni en rouleaux aux imprimeurs, et ont adopté la forme supra-addictive du feuilleton. En se rendant régulièrement au kiosque de son quartier, Alain espère « lire toutes les histoires ». Les albums, chers et épars[1], ne reprennent qu’un infime pourcentage des récits parus. Si d’aventure vous ratez un numéro, une course folle s’enclenche. Quand les messageries de presse[2] ou l’éditeur ne conservent pas les anciens exemplaires, il ne vous reste que l’arbitraire d’un bouquiniste ou les aléas du Vieux Marché. De lecteur insouciant vous devenez – sans crier gare – un collectionneur actif. En s’attachant à ces bandes passantes, ces partitions et alignements de figures, Alain accède rapidement aux principes de lecture.

… en 1ère primaire, je savais lire !

— Alain Van Passen

Malgré sa belle ponctualité, Alain a manqué quelques numéros d’HÉROÏC-ALBUMS et de MICKEY MAGAZINE[3]. Sans se démonter, il se rend aux sièges de ces deux publications bruxelloises. Qu’un enfant de 10 ans brise le mur qui sépare les lecteurs de l’éditeur a dû surprendre. Mais ses parents, Robert, 56 ans, et Mary, 45 ans, sont des familiers du monde de la presse. Lui écrit en néerlandais des romans alimentant le Davidsfonds[4] et des contes pour l’AVERBODE’S WEEKBLAD. Elle écrit en français des récits sentimentaux pour la revue BONNES SOIRÉES et LES BEAUX ROMANS. À deux, ils ont lancé, en 1937, leur propre hebdomadaire : TOPAZE[5]. Marcel Pagnol leur avait donné son accord pour l’utilisation du titre. Les textes avaient été confiés à un imprimeur de Louvain qui les avaient émaillés de nombreuses erreurs de français. Un fiasco légal et financier qui a pesé sur le couple pendant des longues années mais grâce auquel la mention – éditeur responsable – reçoit, pour leur fils unique, une attention toute particulière. Chez les Van Passen, on ne craint pas d’écrire aux éditeurs et… commander.

À Paris, à la croisée de la rue Mouffetard et de la rue SaintMédard, à même les pavés, naît une bourse spontanée d’illustrés menée exclusivement par des enfants. Le journaliste-photographe Noël Bayon décrit, en 1953, cet étrange ballet : « dispersés un moment, les vendeurs et les échangeurs se regroupent l’instant d’après. » Si en France, communistes puis catholiques montrent – avec la loi sur les publications destinées à la jeunesse du 16 juillet 1949 – une belle hostilité envers ces illustrés, le gouvernement belge n’a pas légiféré. Le mot n’y ayant pas cette même ascendance sur l’image[6] et l’influence nord-américaine y étant mieux tolérée[7]. À Bruxelles, pour combler ses manques, Alain fréquente une librairie d’occasion de son quartier, rue de l’Étang, où « il n’y avait aucun adulte, que des enfants ! ». Oscillant entre un commerce privé et une bibliothèque publique[8], le lieu est tenu par une vieille dame.

Qui ne peut s’accroupir, ignore la loi du milieu [9]

— Noël Bayon

« Si on payait un ouvrage 2 francs et que je le rapportais la semaine suivante, elle offrait 1 franc pour un nouvel achat[10] ». Elle ne sort jamais d’argent de sa caisse et propose uniquement « des journaux d’enfants, ce qu’on appelle aujourd’hui des bandes dessinées ». C’est là qu’Alain finit sa collecte d’HÉROÏC-ALBUMS. Sous les instructions de son père, il fabrique lui-même des reliures, arrimant solidement, au fil à coudre, l’ensemble des fascicules si patiemment et diligemment réunis. Pour habiller les cartons protecteurs, ils sacrifient des couvertures d’autres fascicules. Ces volumes sont le noyau de sa collection mais il précise bien : « enfant, je n’étais pas collectionneur !»

Ses humanités gréco-latines, Alain les passe à l’Institut Saint-Boniface, haut lieu de la bourgeoisie belgicaine. Deux influentes figures de la bande dessinée, Georges Remi et André Franquin, l’y ont précédé. Mais contrairement à ces derniers qui ne goûtaient pas aux classiques modèles de plâtre, Alain s’est pris de passion pour l’Antiquité. Après l’école, il commence à suivre, en compagnie d’adultes, des cours de dessin. C’est à deux pas de son domicile, Parc Léopold, dans l’ancien bâtiment de l’Institut d’Anatomie Raoul Warocqué qui abrite le Mundaneum. Le bibliographe Paul Otlet voulait y réunir tout le savoir mondial – essentiellement par ses imprimés – répertorié en microfiches avec mots clefs. Une ambition démarrée dans les années folles qui s’est réduite au fur et à mesure des déménagements et de la disparition de son fondateur en 1944[11]. Fortement marqué par le Alix de Jacques Martin publié dans le journal TINTIN et les péplums italo-américains à la Quo Vadis, Alain conçoit sa propre bande dessinée : Ajax. Ce codex moderne, exemplaire unique, est remarqué par le curateur du Mundaneum qui l’expose sous vitrine. Chaque jour, ce dernier ouvre le meuble, tourne une des pages de la bande dessinée et le referme afin d’encourager les visiteurs à revenir.

Si on peut reconnaître « un joli coup de crayon » à Alain Van Passen, il nous semble néanmoins que sa véritable voie soit la littérature.

— Article Alain Van Passen, conteur et dessinateur, Héroïc-Albums N°11, du 7 mars 1956.

C’est une autre libraire du quartier – qui fournissait à Alain les recueils neufs du journal SPIROU – qui lui conseille de sortir des récits articulés en images pour se mettre à ce qu’elle nomme, « la vraie littérature », celle réduite aux figures de l’alphabet romain. Elle lui prescrit Les travailleurs de la Mer de Victor Hugo. Comme elle, les pédagogues refusent d’admettre qu’une bande dessinée puisse être adressée aux adultes[12], ni même aux adolescents. La culture pour teen-agers, alors en essor aux États-Unis, tarde à s’implanter en France et en Belgique. Le journal préféré d’Alain, HÉROÏC-ALBUMS, cherchait, depuis ses débuts, à s’affranchir de cette infantilisation. Mais sans accès à l’ensemble du territoire français, ce comic-book belge doit se saborder en décembre 1956. Trajectoire également malheureuse pour le journal tabloïd RISQUE-TOUT destiné aux grands frères des petits lecteurs de SPIROU et qui s’arrête après une année chaotique. À 15 ans, Alain est ainsi éloigné de la bande dessinée, réduite à la presse enfantine[13], et se met à dévorer des films et des romans d’épouvante, du fantastique[14] et d’anticipation. Il absorbe cette littérature conjecturale à travers la revue littéraire FICTION. Cette lecture de format poche, découverte en solderie, va, paradoxalement, le faire replonger dans la bande dessinée … définitivement !

Du bizarre au merveilleux, la transition est insensible et le lecteur se trouvera en plein fantastique avant qu’il se soit aperçu que le monde est loin derrière lui.

— Citation de Prosper Mérimée (de son essai sur Nicolas Gogol) placée en introduction du magazine FICTION N°92, juillet 1961.

2 une entreprise qui réunit et distribue les périodiques, reliant les éditeurs aux points de vente.

3 c’est un journal belge qui parut entre octobre 1950 et septembre 1959. Ses lecteurs sont ensuite aiguillés vers LE JOURNAL DE MICKEY français de Paul Winkler.

4 réseau culturel catholique flamand dont les publications fonctionnent par abonnement. Actif sur la Flandre et Bruxelles.

5 un modeste instituteur célibataire, Albert Topaze, est injustement mis à la porte par le directeur de son école. Il entre au service d’un conseiller municipale véreux et de sa maîtresse. Topaze devient un riche – et malhonnête – homme d’affaires. Une pièce de théâtre écrite par Marcel Pagnol sortie en 1928.

6 en France, la Commission Paritaire des Publications et des Agences de Presse (ou CPPAP) exige toujours, dans ses critères d’admission des « Publications enfants et de bandes dessinées » : 10 % de rédactionnel, donc du texte. http://www.cppap.fr/

7 le parti communiste en Belgique va très vite être écarté du pouvoir après la Libération. De leur côté, les catholiques belges ont encouragé une bande dessinée locale dans leurs journaux.

8 une logique qui rappelle les kashi-hon’ya, ces librairies japonaises de prêts de bandes dessinées actives à la même époque. L’on retrouve ce modèle dans plusieurs pays de l’Asie du sud-ouest comme Singapour ou les Philippines.

9 commentaires d’un reportage photographique de Noël Bayon pour l’article Les gamins de Paris ont créé la bourse aux illustrés dans LE FACE À MAIN du 24 janvier 1953. Le texte cite le documentaire de 1951 qui a été tourné sur ce même marché, On tue à chaque page, réalisé par quatre étudiants de l’IDHEC. Le film est ensuite proposé par l’Union Française des Œuvres Laïques pour l’Éducation par l’Image et le Son : l’UFOLEIS. Leur professeur de cinéma était Georges Sadoul, rédacteur en chef de l’illustré pour enfants MON CAMARADE avant-guerre et auteur du pamphlet anti-comics : Ce que lisent vos enfants, Bureau d’éditions, 1938.

10 Alain Van Passen précise d’autres prix en guise de comparaison : une place de cinéma – média alors très bon marché – coûtait 12 fr, un recueil neuf de SPIROU, 50 fr, et une bouteille de Coca-Cola, 5 fr.

11 ce qui reste du Mundaneum est, depuis 1993, abrité à Mons.

12 depuis la fin du 19e, aux États-Unis, des sections de comics étaient insérées chaque dimanche dans les quotidiens. Des récits comme ceux de Flash Gordon, dessinés par Alex Raymond, avec ses inextricables triangles amoureux, s’adressaient aussi aux adultes. Dans les années 30, en Italie, en France et en Belgique, ces pages du dimanche américaines vont être proposées aux seuls enfants, voir adressées uniquement aux garçons.

13 « On le déplore souvent : après l’âge des illustrés et avant celui des romans pour adultes, en dehors des collections coûteuses, les jeunes ne trouvent guère de lectures qui leur conviennent. » Extrait d’un dépliant de lancement de la collection pour adolescents, MARABOUT JUNIOR, dirigée par Jean-Jacques Schellens pour les éd.Marabout, 1953.

14 Le fantastique chez les romanciers belges contemporains est le titre de son travail de fin d’études à l’Institut Saint-Thomas durant l’année académique 1961-1962.

Dona Pursall and Eva Van de Wiele have each contributed a chapter to the collective volume

Dona Pursall and Eva Van de Wiele have each contributed a chapter to the collective volume

New article by Benoît Crucifix in the latest issue of

New article by Benoît Crucifix in the latest issue of